The Sacred Secret: Why Did the Ancient Egyptians Build the Pyramids?

The Sacred Secret: Why Did the Ancient Egyptians Build the Pyramids?

The construction of the pyramids in ancient Egypt was not a random, meaningless act, nor a mere desire to construct massive stone tombs for the glory of kings. Rather, it was a comprehensive humanitarian, spiritual, and philosophical project, through which the ancient Egyptians expressed their religious thought and their profound belief in life and immortality in the afterlife after death. The goal transcended the architectural dimension and touched upon the depths of religious belief and its complex and interconnected philosophical thought among the ancient Egyptians.

The idea of eternal life after death played a prominent role in ancient Egyptian thought and became the focus of many worldly activities at the time. These pyramidal architectural structures represented spiritual temples for resurrection and union with the gods. Their geometric form embodied a philosophical contemplation of a cosmic order founded on balance and harmony between earth and sky, matter and spirit. Therefore, the ancient Egyptians were keen to ensure they enjoyed eternal life while still on earth. They saw in the idea of constructing a fortified pyramidal tomb for the king, above a subterranean burial chamber containing a stone sarcophagus in which the king’s “mummy” was carefully preserved, an eternal guarantee for the continuation of his journey in the afterlife.

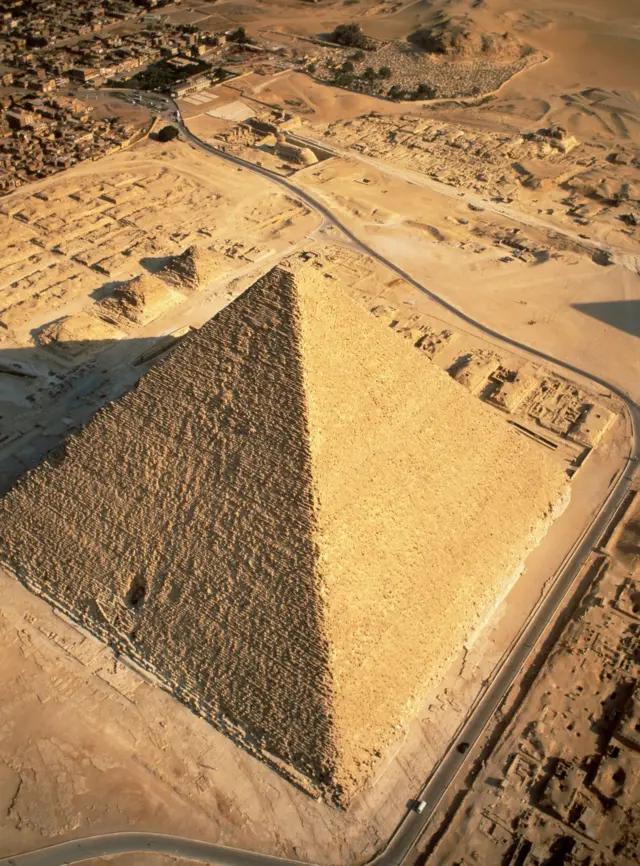

The pyramids and why the Egyptians built them have preoccupied many people for centuries. This has often led them to deviate from the logic of logic. They have surrounded the Egyptian pyramids, especially the Pyramid of Khufu, the largest pyramid in Egypt, with a wealth of exciting stories and myths about their construction method and functional role. This has led some to question the identity of those who built them, as well as other stories that are not based on historical or scientific foundations.

Here, we seek to answer some questions, including: Why did the Egyptians resort to the pyramidal shape to preserve the bodies of kings? What was the religious and philosophical significance of constructing these massive stone blocks that transcended the limits of their architectural engineering? Were the pyramids used solely as tombs, or did they have other, broader funerary functions? Did races other than the Egyptians contribute to their construction? Finally, were they built through “forced labor and torture,” as some have claimed?

“Ascending to the Sun”

The question often arises: Why did the ancient Egyptian kings want to build their tombs in the shape of a pyramid? The answer lies in the fact that they saw this particular architectural form as the truest expression of their belief in the solar cult, which was the core of ancient Egyptian religious belief. They saw the shape in general, and the pyramidal summit in particular (called “benben” in ancient Egyptian), as an embodiment of the sun’s rays descending toward the earth. They therefore wanted to bury their kings in tombs shaped like the sun’s rays, which they hoped to ascend to upon the day of resurrection, according to ancient Egyptian religion.

During the Old Kingdom (3150-2117 BC), the king of Egypt was considered a “god.” As a sacred being, the king naturally held all power in his hands. The monarchy in ancient Egypt occupied a special and distinct section within the boundaries of the religion itself, a fact confirmed by the architectural forms of this period, such as the pyramids. The arrangement and distribution of buildings also demonstrates a close relationship that unites the god Ra (the sun god) and the king (the god), and sometimes even confuses them.

It seems that the pyramid did not enter the scope of the sun cult until the era of the Fourth Dynasty (2520-2392 BC), according to the division of ancient Egyptian history into ruling dynasties through its stages, as the outer borders of the triangle’s lines symbolize the rays of the sun, which were sometimes represented by a bundle of lines, sometimes connected by hands at their ends (as happened in the art of Tell el-Amarna during the era of King Akhenaten 1360-1343 BC).

Iskandar Badawi says in his study, “The History of Architecture in Ancient Egypt,” that “in the Middle Kingdom (2066-1781 BC), the upper buildings of the tombs took a pyramidal shape, the top of which was in the form of a pyramid (a diminutive of pyramid), on which were engraved two eyes (Udjat) and then a text asking the dead to appear and see the Lord of the Horizon (the sun) when he travels across the sky.”

The solar influence is also noted, according to Badawi, in the presentation of various elements such as sections where solar rituals were performed in the funerary temple of the pyramid, and in the burial of wooden boats discovered at the site.

“The Road to Eternity”

The Egyptians called the pyramid “mer” in the ancient Egyptian language, which means “place of ascent,” a clear indication that reflects their belief that the pyramid was a means for “the king’s soul to ascend to heaven to unite with the god Ra.” The name pyramid in many European languages is also derived from the Greek word “pyramis,” meaning “triangular piece of bread.” This word was coined by the Greeks to approximate the pyramidal shape in their language when they visited Egypt. Some believe that the word “pyramid” is an ancient Semitic word meaning a geometric shape with four sides that meet at a central point at the top. This required the ancient Egyptians to undergo many experiments and attempts to achieve the final pyramid-like shape known today in their tomb.

The earliest hints of the idea of building a pyramid began with an older stone building known as a “mastaba” during the First Dynasty (3150-2890 BC), which had widened corners at the bottom and narrowed as its sides rose.

This required the engineers to undertake many architectural experiments, which were crowned with success during the reign of King Sneferu (Neb-Maat) (the first king of the Fourth Dynasty, 2520-2470 BC). This was when his engineers succeeded in achieving the complete pyramidal shape of the tomb, known as the Red Pyramid in the Dahshur area, and what followed of more massive complete pyramids, most notably the Pyramids of Giza.

The pyramid was the “road to eternity” and a means for the king to ascend to heaven, as we mentioned, especially since the Egyptians believed that death was not the end of the road, but rather the beginning of another life and a journey for the soul to the world of eternity. The pyramid was considered a “heavenly staircase,” as clearly embodied by the architectural form of the step pyramid built by King Djoser (the first king of the Third Dynasty, 2584-2565 BC). It was built in the form of steps of a ladder “on which the soul of the deceased king ascended to heaven to unite with the god Ra,” the sun god, who represents light, resurrection, and eternal life.

Some scholars believe that the pyramid, in addition to its solar symbolism, was also a symbol of the divine energy that “lifted the king’s soul to heaven.” After his death, the king transformed into Osiris, the god of the afterlife, becoming immortal like a god and a partner in his daily journey across the heavens. The pyramid’s design served this idea.

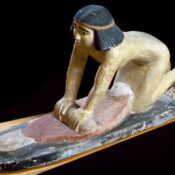

When building the pyramid, the Egyptians were keen to make it a safe repository for the body of the deceased king, in order to protect his soul and ensure its continuation in eternal life. This was due to the extremely important position the body held in Egyptian belief. They believed that the human body consisted of several elements, the most prominent of which were the body, the visible side, and the “Ba” (soul), which is the person’s personality in the spirit world. It was always depicted in the form of a bird with a human head bearing the features of the deceased person himself, in reference to his person and soul when it left the body after death to heaven. The “Ba” would return to visit the body from time to time.

The third element in the human body is the “Ka” (double). The Egyptians believed that it was a material spirit born with the human being, from a light, invisible substance, like air, that took the form of its owner and was an exact replica of him. After death, the “Ka” remained with the body until the “Ba” returned, and the two joined together, the “Ka” and the “Ba,” after which the deceased entered the fields of eternal bliss, which were called the “Yarrow” fields, if the person successfully passed his trial on the Day of Judgment, or his eternal damnation if he was convicted in that trial.

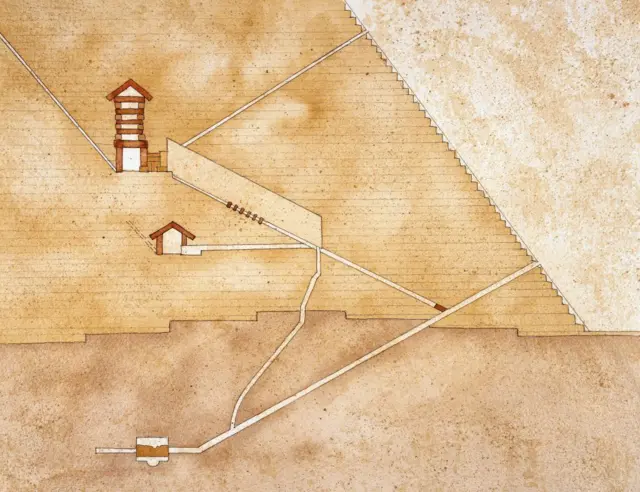

Accordingly, the Egyptians believed that the Ba and Ka, the spirit and its companion, could not continue their journey towards eternity without a preserved and intact body. Therefore, the pyramids were built with designs that ensured the highest levels of security to protect the mummies of the kings from tomb robbers and natural elements, ensuring that the king’s soul would return to the body during the rituals of resurrection and immortality. This prompted the architect to design complex internal burial chambers and secret passages, equipped with offerings, statues, and sacred texts that would aid the king in his journey to the afterlife.

The Egyptians were careful to furnish these burial chambers with a complete set of tools and furniture used by the king in his earthly life, as well as quantities of food, in order to preserve the body and its “ka” companion for eternal life in an atmosphere similar to that which the person was accustomed to on earth.

The idea of building the pyramid was also linked to another religious symbolism that embodied the theory of the creation of the universe, known as the “eternal hill,” which holds that the world, before the beginning of creation, was an ocean of water, called in ancient religious thought (Nun), when there were no humans or living beings. Within this ocean was a hill, and the god Ra, the sun god, was able to create himself, and from within this “eternal hill,” he created the entire world and began the formation. Therefore, the pyramid was considered a symbolic representation of this sacred hill, which gave the pyramid a more sacred cosmic dimension. Thus, the pyramid became a sacred place for the ancient Egyptians and an intermediary between his worlds.

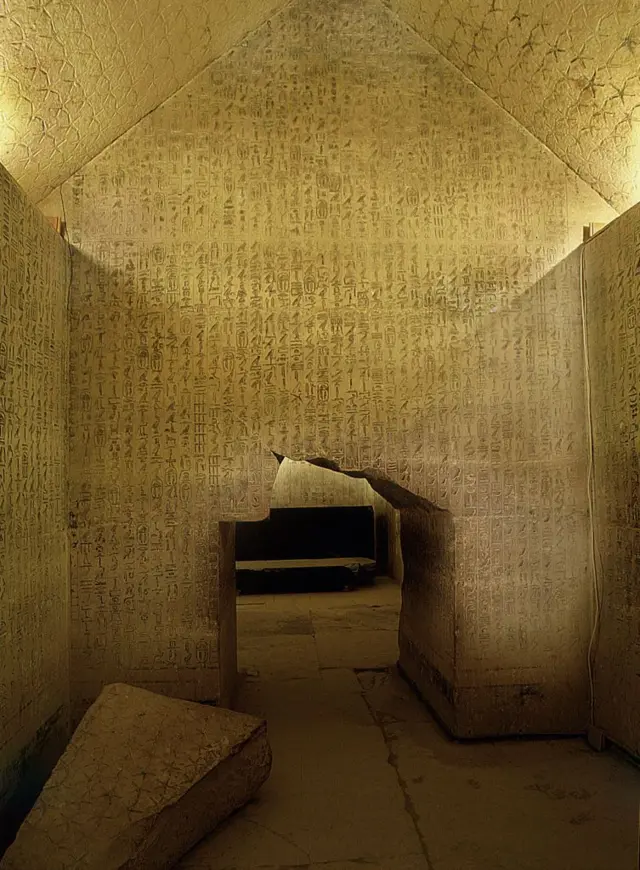

Among the most prominent texts indicating the profound religious symbolism of the pyramids are what are called in religious literature the “Pyramid Texts.” These are the oldest written sacred religious texts in the world, and they first appeared in the pyramids of the kings of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties (2392-2117 BC) in Saqqara.

These texts contain prayers, hymns, and incantations intended to facilitate the king’s passage to the afterlife, protect him from evil spirits that might encounter him during his journey, and enable him to unite with God. These texts also explain how the king was transformed into an “immortal star” in the sky, a religious image that embodies the idea of spiritual immortality.

In her study, “The Pharaohs in the Time of the God-Kings,” French scholar Claire Lalouette cites excerpts from these texts about the scene of the king’s ascension to heaven. We mention, for example, the following: “How beautiful it is to see the king, his forehead tied with a headband like (the god) Ra, and his kilt like (the goddess) Hathor… while he ascends to heaven among his fellow gods.”

The text adds: “How beautiful the vision is, how majestic it is to contemplate this god when he ascends to heaven, as his father Atum (the god) ascends to heaven, the Ka above him, the charms of his magical methods beside him, and the fear he arouses in souls at his feet.”

The pyramid was also the central building in a vast complex that included a number of wooden boats placed in parallel pits, as was the case with the pyramid of King Khufu, which are called “sun boats,” and which enabled the king to travel across the sky to join Ra in the “Land of Light.”

“Architecture for Eternity”

The kings of the Early Dynastic Period built their tombs in a rectangular shape above ground level, built of mud bricks and called a “mastaba.” The royal tomb evolved during the Old Kingdom, from the stepped form during the reign of Djeser and Sekhemkhet at Saqqara to the two-story pyramid during the reign of Huni at Meidum, to the broken-sided pyramid during the reign of Sneferu at Dahshur, and finally to the complete pyramid for the first time in ancient Egyptian architecture during the reign of Sneferu.

This artistic development in the architecture of royal tombs indicates that it was “local and Egyptian,” not influenced by any foreign thought, as some have promoted. This refutes myths that attribute the construction of the pyramids to other peoples or individuals from a continent that sank into the Atlantic Ocean, as well as other stories that have no historical or logical basis.

In his study, “Ancient Egyptian History,” Ramadan Abdo believes that the reason royal tomb architecture reached this level of grandeur and perfection was due to two factors: “The first was the sanctification of the king, as people had to erect a grand structure for him from which he could overlook the other world, just as he overlooked them in this world, towering and high, visible to people everywhere. The second was the Egyptians’ love of the arts, which drove them to find new attempts at developing tomb architecture.”

The first known architect of ancient Egyptian architecture is the engineer and vizier Imhotep (Third Dynasty 2584-2520 BC), the architect of the step pyramid of King Djeser at Saqqara. He oversaw the king’s architectural complex and is credited with initiating the use of stone instead of brick and wood, which had previously been used.

There is no doubt that Imhotep employed a large number of workers for this massive undertaking, who were provided with food, drink, clothing, shelter, and the necessary care. His architectural ensemble and approach served as the first building block for architectural development that others followed during later royal eras, resulting in the construction of the greatest pyramids and stone monuments.

In his study, Ramadan Abdo Ali believes that “Imhotep’s initial idea was to construct a mastaba-like tomb. It appears that Imhotep was influenced by religious ideas that led him to transform it into a step pyramid, perhaps to represent the king’s ascent towards the sun temple and the heavenly realm.”

Royal tombs were initially devoid of any inscriptions. Starting from the Fifth Dynasty (2392-2282 BC), inscriptions were carved on the surfaces of the walls of the burial chambers and adjacent passages, to serve as charms to help the deceased king, when he ascended to heaven, such as the pyramid of Unas in Saqqara during the period 2312-2282 BC. As for the mastabas, their walls were covered with inscriptions and texts in order to allow the deceased to relive, for eternity, selected moments of his life that he lived on earth.

The king was also careful not to build his pyramid in isolation from the world he had inhabited before his death. Thus, the pyramids of the kings and the smaller pyramids of the queens were grouped in long rows, at the edge of the desert, all facing west. The tombs of the royal court, with their rectangular upper structure, were arranged along what looked like “streets” so that the king’s entourage would not be separated from their king and patron after death.

In his study, “The Civilization of Pharaonic Egypt,” French scholar François Dumas says, “We should not think that the pyramids were merely tombs. They gathered around the king, in the afterlife, various activities that were known in the surrounding environment.”

He adds: “We find that since the first two dynasties, the tombs of individuals were not far from the royal mastabas, but we are not able to clearly understand the significance of these funerary buildings, except from the reign of King Djeser, and their purpose was to serve the (Ka) of the king and those surrounding him in eternity.”

“Thus, from Meidum in the south to Giza in the north, the fields of pyramids of the kings of Egypt were lined up, starting from the Fourth Dynasty to the Sixth Dynasty (2282-2117 BC),” says Lalouette in her study. “During each of these eras, the life of the state was centered around the pyramid. Indeed, whenever a king ascended the throne, a new headquarters was established, and work was intensified to build a new pyramid.”

In his study, Iskandar Badawi points out that the great difference between the various ritual buildings in the complex of King Djeser, and the elaborate planning of the funerary temple of the pyramid of King Khafre (2437-2414 BC), from the Fourth Dynasty, indicate “a long period of development, both architectural and intellectual.”

As for the number of pyramids in Egypt, Egyptian scholar Zahi Hawass indicates in his study “The Miracle of the Great Pyramid” that “the number of pyramids reaches approximately 118 pyramids spread from Aswan in the south to Abu Rawash in the north.”

Did kings build their pyramids by enslaving and torturing workers?

Some Western scholars have long promoted claims that Egypt’s pyramids were built by “slaves,” a claim that reinforces the notion of “exploitation and oppression” in the construction of the greatest architectural marvel in history. However, recent archaeological discoveries and ancient Egyptian texts have revealed a completely different picture: a society known for organization and precision, and one that provided workers on major projects, such as the construction of the pyramids, with living rights that reflected a deep appreciation for their role.

Evidence from construction sites such as Giza and Deir el-Medina indicates that the workers involved in building the pyramids were not state slaves, but rather skilled laborers who lived in specially designated housing and received food, healthcare, and rest periods. Some texts and inscriptions also reveal the names of the work teams and some leaders who were honored after their deaths, dispelling the stereotype that has long been associated with their efforts.

Greek travelers, led by the historian Herodotus, were the first to contribute to the spread of myths that spoke of the use of a system of “forced labor and inhumane treatment” and the kings forcing the people to build buildings such as the Pyramid of Khufu, for example.

In his study, “The History of Ancient Egypt,” the French scholar Nicolas Grimal provides an example of these Greek myths and some of what Herodotus claimed, such as: “(Khufu) committed no evil. He began by closing all the temples, forbidding the Egyptians from offering sacrifices, and ordering them to work for him… They worked in groups that alternated every three months, each group consisting of 100,000 individuals… The work on building the pyramid itself took 20 years.”

In his criticism of Herodotus’ statement, Grimal points out that the flood season and the rise in the Nile’s water level were a time when the labor force placed itself at the king’s disposal in fulfillment of the right of authority he had over them, adding: “The peasants constituted the majority of the labor force at that time, and under these conditions of seasonal work.” Grimal added that Herodotus “liked to highlight the harshness of his rule in his accounts of Egypt.”

It is worth noting that Egypt at that time was primarily an agricultural country, and that agricultural land was largely owned by the king and temple priests. However, this does not negate the existence of private property owned by peasants who lived within the limits of their land’s production. The peasant’s labor was subject to the mercy of the Nile flooding, which regulated his social and professional life.

The ancient Egyptians were governed by spiritual and religious motives in every aspect of their lives, including the work they did in constructing massive stone structures like the pyramids. Those who promote the idea that kings used forced labor to build their tombs and monuments thus forget that these spiritual motives were the primary driving force behind all behavior, at the individual, group, and state levels.

In his study, “Zionist Fallacies and Slanders Against the History and Civilization of Pharaonic Egypt: A Response and Refutation Based on Archaeological Evidence,” Abdel Moneim Abdel Halim Sayed, professor of ancient history at the Faculty of Arts, Alexandria University, says that the spiritual motives of the ancient Egyptians were evident in their belief that “they would be resurrected after death and live a life in the afterlife that was completely identical to their earthly life.”

He adds: “One of the most important pillars of this belief is the belief of the ancient Egyptians that the pharaoh who lived under their care in this worldly life is the same pharaoh who will live under their care in the afterlife after resurrection, and that the more sincerely they served this pharaoh in this worldly life, and at the forefront of the manifestations of this sincerity was contributing to the construction of his tomb, which would protect his body so that the pharaoh would have the opportunity to be resurrected, then this would be met with the lavishness of this pharaoh’s blessings upon him in the afterlife.”

He adds: “Hence, when Egyptian workers lifted heavy stone blocks, they believed that this work would guarantee them a happy afterlife. This belief provided them with spiritual energy that was many times greater than the material incentives of generous wages or attractive rewards.”

French researcher Lalouette confirms this view in her study, saying: “The construction of these gigantic buildings did not require, as the Greeks claimed, and as Hollywood films want to portray, the use of hordes of slaves who were severely beaten with whips.”

She added, “The workers who built the pyramids were exclusively Egyptians. Most of them were farmers who were recruited alongside soldiers who left behind some army units, as indicated by some inscriptions they drew on stone blocks that are still visible today.”

Lalouette asserts that these men were working to secure the eternity of “the divine king and its protections, and they were fully aware of the importance of their work, motivated by a firm faith that would later motivate the efforts of cathedral builders in Western Europe, hundreds of years later.”

In his study, “The Miracle of the Great Pyramid,” Egyptian scholar Zahi Hawass notes that the pyramid “was Egypt’s national project, and everyone participated in it, because the people must participate in the king’s being a god.”

He added, “The discovery of the tombs of the pyramid builders confirmed that they were not forced to build the pyramid. This is evidenced by the fact that they built their tombs next to the pyramids and placed artifacts inside them that would help them survive in the afterlife, just like kings, princes, and officials.”

Hawass says, “The workers who transported the stones were paid by families spread throughout Upper and Lower Egypt, as a national duty to participate in the completion of the national religious project. As for the foremen, artists, and sculptors, they worked for the king and were paid by the state. Their wages consisted of barley, wheat, and beer.”

He added in a previous interview with Al-Ahram newspaper: “Based on what we’ve found, we believe the number of workers involved in building the pyramid is approximately 10,000, working throughout the day and being replaced as needed by extended families who provided them with food and other supplies.”

Hawass said: “The number of workers increased during the Nile floods, which submerged agricultural lands, leaving farmers unable to find work. They turned to building the pyramid, which was one of the most important reasons for the growth of Egyptian genius in construction and civilization.”

Tombs have also been discovered, providing new archaeological evidence of the religious life of the workers. Other texts indicate that families in Upper and Lower Egypt sent 11 calves and 23 sheep daily to support the workers, while the state did not collect any taxes from them in return.

There is no doubt that the discovery of the tombs of the pyramid builders on the Giza Plateau represents a turning point in shedding light on the nature of the work, and it provided evidence that completely and unequivocally refutes all indications that construction was subject to a labor-force system. First, these tombs are located directly next to the “royal” pyramid complex at Giza, which has led some scholars to support the view that the king may have ordered his workers to be buried next to him out of loyalty to them, without class distinction, as he did with his entourage, as we mentioned.

Ramadan Abdo Ali adds in his study: “A bakery was found where those in charge of these tombs prepared bread and distributed it to the workers along with garlic and onions. Pottery plates were also found for serving food to the workers.”

He added: “To the east of these graves, the remains of two villages were found. One was inhabited by workers, and the other by artists and supervisors.”

It is well established that the authority responsible for building the pyramid replaced workers every three months, without disrupting their primary work of cultivating the land. Remains have also been found indicating that workers sustained work-related injuries and underwent treatment. Some of these work-related injuries even required surgical treatment for fractures, indicating that the state provided a comprehensive healthcare system for these workers.

The Egyptians built their pyramids to ensure eternal life for their kings, in accordance with a complex and interconnected religious belief. They represented a structure that combined architectural, religious, and philosophical functions. For them, they were not merely massive buildings erected in the heart of the desert outside the city limits. Rather, they embodied a civilizational vision and a deeper religious outlook. They were simultaneously a tomb, a temple, a symbol, and a path to heaven

All Categories

Recent Posts

Oblicze Króla Sprzed Trzech Tysięcy Lat – Mumia Setiego I

3,000-Year-Old Elegance: The Mummy with Perfect Braids

World Baking Day… A Tribute from the Heart of Ancient Egypt! 🍞🇪🇬

Tags